With more than two decades in the business of IP geolocation, we spend a lot of time thinking about accuracy, but, as with all things big data, a simple question (“How accurate is IP geolocation?") usually has a complex answer. In this post, we’ll talk about some common assumptions about how IP geolocation works and contextualize those assumptions in light of the structure of the internet and the distribution of the IP space across geographical regions. In light of these considerations, we’ll develop a deeper understanding of the constraints and opportunities for IP geolocation.

Is IP geolocation about a pin on a map?

When we start thinking about IP geolocation, we might imagine a process of pinpointing, with some accuracy, the location of an end-user on the internet. On some level, it makes sense that we would think about it this way because a lot of applications of IP geolocation are based on the premise of finding an end-user’s true location in the world. There’s often a lot riding on your ability to locate the user with confidence. Targeting your content to users accurately can mean a significant increase in revenue, less friction for your customers, and in some cases the preservation of lucrative licenses and business relationships. Whether you’re localizing content, implementing geofencing, or gathering data for security and analytics, you start with an IP address and hope for something like the latitude and longitude of the end-user.

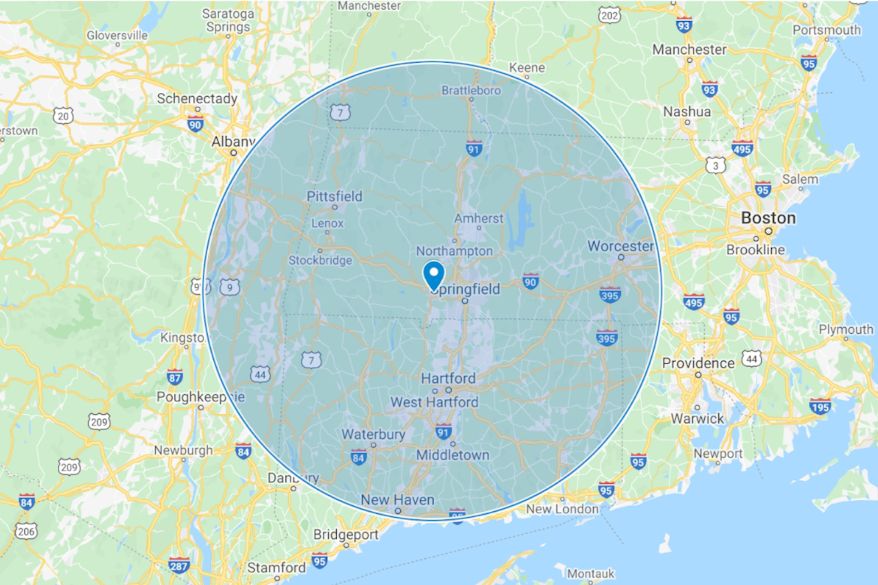

All of our IP geolocation data comes with an accuracy radius field. The actual geolocation of the IP address is likely within the circle with its center at the geolocation coordinates and a radius equal to the accuracy radius field. While the pin on the map might lead us to think that the IP address is close to the center of this circle, in reality we’re defining a region in which the IP address is very likely to be.

Our data does a good job of estimating the approximate location of IP addresses (see the accuracy for our GeoIP City database). But if you use any of our geolocation or fraud prevention products you’ve probably already seen the caveat we post throughout our documentation, that our data is never precise enough to locate the street address of a particular household. If you start with the premise of finding an end-user’s location, you might wonder why we repeat this disclaimer so often. Will we be able to improve GeoIP data so that, one day, we can locate street addresses? Do we already have a method to produce that kind of data, but withhold it for legal and ethical reasons?

While it is possible to map some IP addresses to street addresses, one of the major constraints on the accuracy of IP geolocation has to do with the infrastructure of the internet itself and the nature of IP addresses.

Understanding IP addresses

There are tools to find your IP address all over the web, including on our website. The phrase “your IP address” might lead you to believe that the IP address being located is really yours in the same way that a street address is yours. You may imagine that when you sign up for internet service, your ISP assigns you an IP address, and this IP address is your gateway to the internet until you move, or switch ISPs. This assumption may be reinforced if you infrequently check your IP address using one of these tools and notice that the address seems to remain the same. People often extend this assumption from the IP address of their personal computer to all kinds of devices that communicate online, from smart TVs to phones, leading them to imagine a relatively stable structure of IP addresses communicating across the web—but the reality is that IP addresses are far more mutable than this assumption would lead you to believe.

Both IP addresses used to serve content and receive it vary greatly, in terms of how frequently they may move location, who may be using them, and whether they are directly associated with the end-user or organization doing the communicating.

Content server IP addresses

When we dig just beneath the surface of the internet, the variability of IP addresses becomes obvious. People tend to understand this more readily when they think about servers hosting content instead of end-users browsing that content. A lot of people have a basic understanding that websites and applications may be hosted on computers that aren’t owned and operated by the organization that develops and maintains the website. We understand that many websites from different organizations may be hosted from the same data center server.

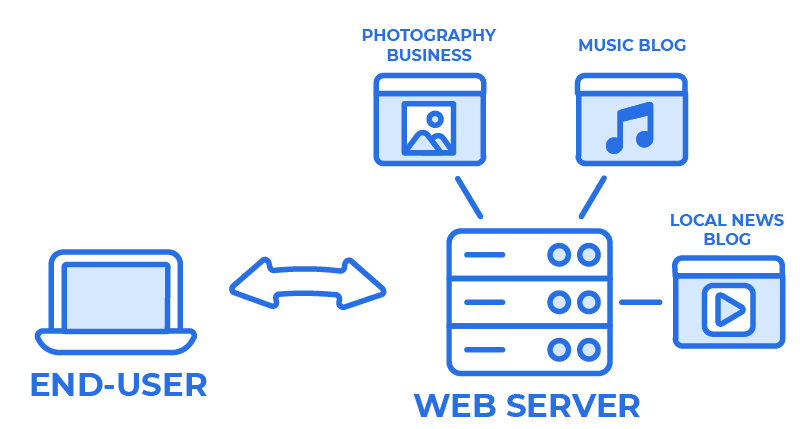

Whenever you go to a website, your device makes a DNS request, essentially asking “What IP address should I access for the content at this domain name?” It isn’t surprising that the IP address returned is the same for multiple domain names. Many of us know about name-based virtual hosting, for example, which allows content for multiple different domain names to be served from a single IP address. If you aren’t familiar with this terminology, Wikipedia has a good overview, but even if you’re not familiar with the phrase you may have used this technology. If you’ve ever set up a simple web hosting solution, you probably had to enter an IP address from your web hosting server into the domain name server where you purchased your domain. In this case, you may host more than one website on a single server, providing the same IP address for multiple domain names.

A web server may host several very different sites or apps behind a single IP address.

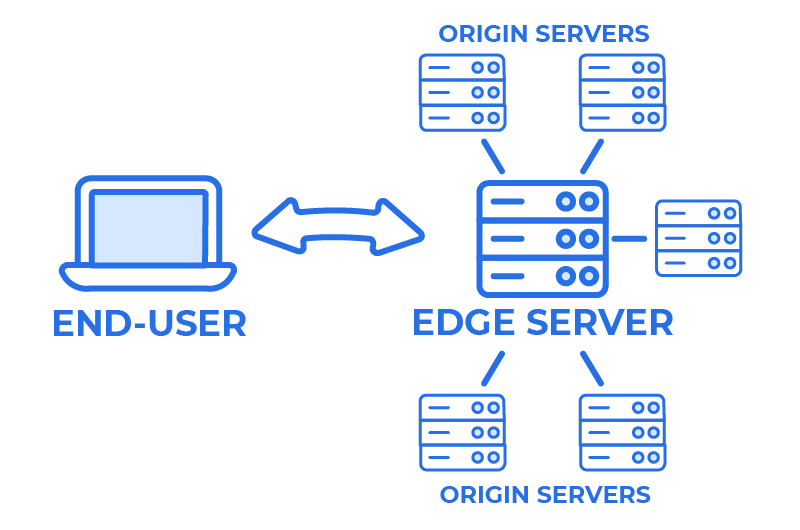

On a grander scale, content delivery networks (CDNs) like Cloudflare serve a high volume of domain names from a small set of IP addresses. These IP addresses point to “edge servers” that cache content and provide increased security, acting as intermediaries between the end-user who is requesting content, and the origin server (with its own, distinct IP address) that hosts it. CDNs may add, move, or change the edge servers that provide content to end-users, and as they do so the IP address associated with a website can change as well. If you want to learn more, software developer Nicholas C. Zakas has a great overview of CDNs.

In a content delivery network, the end-user communicates with an edge server, which in turn communicates with many origin servers that host content. In these cases, the end-user knows the IP address of the edge server, but not the actual origin server that hosts the website or application they’re trying to access.

In all of these cases, the end-user never needs to know the IP address of the origin server providing them with content. Even if the origin server that hosts the content of a website has a single, fixed geolocation, the end-user would have no way of knowing that location based on the IP address they were communicating with.

Residential and business IP addresses

It’s easy to understand why a content server’s IP address would change or would be linked to a device in a different location from where the content was hosted and maintained. What about end-users? One of the first things that may come to mind when we ask this question are VPNs (virtual private networks).

VPNs and other proxies

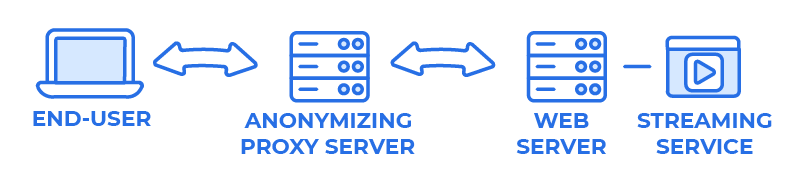

Almost anyone can sign up for an account with a VPN, allowing end-users to route their outgoing requests through an anonymizing network of intermediary servers. These servers function similarly to the edge-servers of CDNs discussed above. The end-user’s requests are routed to a server, often located in a data center or hosting facility. That server relays the end-user’s request for content, and the website or application that receives the request only sees the IP address associated with the server.

In spite of their sometimes questionable reputation, people use VPNs for any number of reasons. Due to effective advertising and media coverage, VPNs have entered the consciousness of a broader section of the general public and VPN usage continues to see an upward trend. It’s true that fraudsters and digital pirates may use VPNs, but privacy-conscious end-users may also use a VPN to protect their identity from casual data-gathering, express political dissent, or circumvent censorship.

When people use an anonymizing proxy, a server makes requests for content on behalf of the end-user. This means that the server’s IP address is being used to browse the internet, not the end-user’s, and it is not possible to determine the geolocation of the end-user.

To make matters more complicated, VPNs are only one kind of proxy an end-user might use to browse the internet. As more people work from home, corporate proxies may be used to protect access to sensitive data. Residential proxies, which function like VPNs but use computers and devices on residential internet connections, instead of servers in hosting centers, to route traffic. These residential proxies are becoming more popular, and they’re increasingly difficult to detect.

The use of VPNs and other proxies for work or privacy effectively masks the IP address of the end-user so that their true geolocation cannot be accurately determined. Only the IP address of the proxy can be geolocated, and often this isn’t what you’re looking for at all. You can read more about VPNs and other anonymizers on our blog. We provide solutions for proxy detection through the GeoIP Anonymous IP database, GeoIP web service, and the minFraud Insights and Factors services, but geolocation of the end-user isn’t possible.

Static IPs and multiple users

IP geolocation of end-users is complicated even when a proxy isn’t involved. While it may be easy to think of the IP address assigned to us by our ISP as “belonging to us” in the way that a street address belongs to a house, this isn’t the case. Many of us have heard of the difference between “static” and “dynamic” IP addresses (if you haven’t, there’s a good primer on Lifewire). Most residential IP addresses are dynamic, and ISPs reassign these for any number of reasons. ISPs will sometimes offer static IP addresses as an additional service to their customers, but even in these cases the IP addresses only remain fixed to a particular geolocation as long as the customer continues to subscribe to this service.

To make matters more complicated, ISPs do not always move IP addresses within fixed geographic areas. While some IP addresses remain in a particular region for long durations of time, this can change suddenly due to business, technical, or even automated decisions made by ISPs to help manage their infrastructure. In this way, it’s better to think of the distinction between a static and dynamic residential IP address less as a binary and more as a spectrum. The question isn’t whether an IP is dynamic, it’s a question of how dynamic it is. At some point its geolocation may be subject to change, even if that’s because an end-user moves house and no longer retains the same static IP.

Internet service providers have a huge portion of the IP space to distribute among their customers. They may change the IP address of an end-user for any number of reasons.

In addition to reassigning IP addresses, there are a number of circumstances in which an end-user may share an IP address with others. In the same way that name-based virtual hosting allows multiple domain names to be served by a single IP address, ISPs sometimes place multiple end-users behind a single IP address, often in offices, apartment complexes or other spaces where the infrastructure for internet access is more deeply integrated into the construction. As a result, the number of end-users associated with an IP address should also be understood less as a static, knowable quantity, and more as a shifting scale with some IPs being used by very few people, and others being used by a high volume of end-users.

Mobile and other kinds of end-users

Mobile users present additional challenges to IP geolocation. Cellular ISPs may be even more flexible in the geographic standards by which they assign IP addresses. Even when those IP addresses remain tied to particular coverage areas, the end-user is often, well, mobile—commuting or walking across areas that could never be reduced to a single street address. When people use the internet on the go, they may also rely on public or paid wifi networks as much as they rely on their cellular data carriers. Android phones even come with a feature that prompts users to connect to public wifi networks via a VPN, and some ISPs offer public wifi hotspots to their subscribers as a perk. Mobile users conscious of their data consumption may jump from network to network, whether as part of a day to day routine or while vacationing. A single device in these cases may jump between an IP address assigned to a cellular region, to one assigned to a cafe, back to their cell network, to a grocery store, back to their cell network, and then to their home wifi network.

Mobile users may be assigned several different IP addresses as they travel, as they browse using their cellular data plan and public wifi available at a variety of businesses.

More and more people browse, shop, and even perform sensitive transactions like banking from their smartphones. This means that applications that rely on geolocation data to deliver an efficient, secure customer experience have to reckon with the complications posed by mobile usage. Some applications may attempt to get more precise location data by relying on a device’s GPS location permissions, but end-users are increasingly reluctant to grant location access even to applications from well-known businesses. Businesses have to choose whether they want to lose potential customers who are unwilling to grant location permissions or learn how to understand and leverage IP geolocation data as a fallback or alternative.

The impact of privacy opt-outs on IP addresses

Under a number of laws and regulations (e.g. GDPR and CCPA), individuals may request to opt out of the sale of their personal information which includes IP address data. Although these regulations are generally meant to protect the privacy of individuals, and MaxMind data cannot be used to locate individual people, we honor these data privacy requests in compliance with local and international regulations.

When MaxMind receives a valid opt-out request, we remove the IP address from most of our databases. MaxMind does sell specialized databases (GeoIP Shield) which contain these IP addresses, and which can only be used for specific use cases in which these regulations do not apply—fraud prevention, compliance, and many security use cases. If you are interested in GeoIP Shield, please contact enterprise@maxmind.com or your MaxMind Customer Success Manager to discuss if this specialized database is suitable for your use case.

An IP address may be missing for reasons other than data privacy requests. An IP address may not be routed on the internet, or MaxMind may exclude some ranges for other reasons. MaxMind is unable to confirm whether an IP is missing due to an opt-out request for privacy reasons.

Rethinking IP Geolocation Accuracy

The first step in learning how to leverage IP geolocation is understanding the nature of IP addresses and the underlying infrastructure that connects them. We need to set aside our basic preconceptions of the internet as a highly-ordered grid of stable routes and end-points. Even in the case of a straightforward request from an end-user without a VPN to a content host, a complicated relay may ensue. The end-user may share an IP address with several other users, or they may be switching between IP addresses as they travel, and the content host may be serving its resources from a shared origin server that hosts many sites to an edge-server in a CDN. This relay of requests introduces complexity into the question of, “Where on Earth is this IP address located?”

Complexity doesn’t mean that IP geolocation can’t be done, but in order to use it effectively we have to understand its limitations. Geolocation also isn’t the only tool in your toolbox when it comes to analyzing IP addresses. In addition to geolocation, MaxMind offers IP intelligence data and tools that can help you to (among other things) contextualize and make better use of geolocation data itself. These tools include things like an accuracy radius that comes in all of our GeoIP City products and services, as well as confidence factors in our GeoIP Enterprise database. Looking beyond raw indicators of accuracy, we provide a diverse array of IP intelligence data through GeoIP products and web services that can be used to help answer the underlying questions that you may be attempting to answer with geolocation—questions like, “What content would be most advantageous to serve this customer?” or “What can I learn about trends in this user’s behavior?”

In the coming months we’ll dig a little deeper into how we assess the accuracy and confidence of our GeoIP products. We’ll also talk about how we structure our data to be as valuable as possible to our customers, in light of what we know about the structure of the internet. And we’ll dive deeper into the concept of IP intelligence, to help you learn how to reshape and expand the questions you’re asking about IP addresses to get answers that you can use with confidence.